SpaceX launched a Falcon 9 booster for a record-breaking 13th time Friday from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, hauling 53 more Starlink internet satellites into orbit as astronomers renew concerns about the growing brightness of the latest generation of the broadband relay spacecraft.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) Falcon 9 rocket lifted off from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center at 12:09:20 p.m. EDT (1609:20 GMT) Friday. The Falcon 9 steered northeast from Florida’s Space Coast to arc downrange over the Atlantic Ocean, aligning itself with the orbital inclination of SpaceX’s Starlink satellite fleet.

Two-and-a-half minutes later, the Falcon 9’s first stage shut down its nine kerosene-fueled engines and detached from the upper stage. The booster unfurled titanium hypersonic grid fins and headed for a drone ship parked in the Atlantic east of Charleston, South Carolina.

The Falcon first stage reignited a subset of its engines for two braking burns before settling onto the deck of the recovery platform “A Shortfall of Gravitas” to complete its 13th trip to space, a record for SpaceX’s fleet of reusable rockets.

Meanwhile, the upper stage guided the 53 flat-packed Starlink satellites — each more than a quarter-ton — into a preliminary transfer orbit. The Falcon 9’s upper stage released the 53 spacecraft about 15 minutes after liftoff, notching another successful launch for SpaceX.

The first stage booster flew Friday — tail number B1060 — debuted in June 2020 with the launch of a U.S. military GPS navigation satellite. Since then, the booster has launched Türksat 5A communications satellite, SpaceX’s Transporter 2 small satellite rideshare mission, and now 10 Starlink missions.

The launch Friday was the first of three Falcon 9 missions scheduled in just 36 hours. Another Falcon 9 is set to take off from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on Saturday with a German military satellite, and SpaceX’s launch team will return to action early Sunday at Cape Canaveral with a mission to deploy a commercial Globalstar communications satellite.

In order to save time, SpaceX no longer performs test-firings before most of its launches, after seeing good performance of its reusable boosters mission after mission. Engineers are also streamlining refurbishment and inspections on boosters between flights, according to a report published this week by Aviation Week & Space Technology.

According to Aviation Week, SpaceX has qualified its reusable Falcon 9 boosters for at least 15 missions, up from the 10-mission goal the company stated when it debuted the Block 5 booster — the latest iteration of the Falcon 9 — in 2018.

The magazine reported SpaceX put booster components through vibration testing to four times the fatigue life of what they would experience over 15 flights, giving engineers confidence that the rockets will continue to fly successfully.

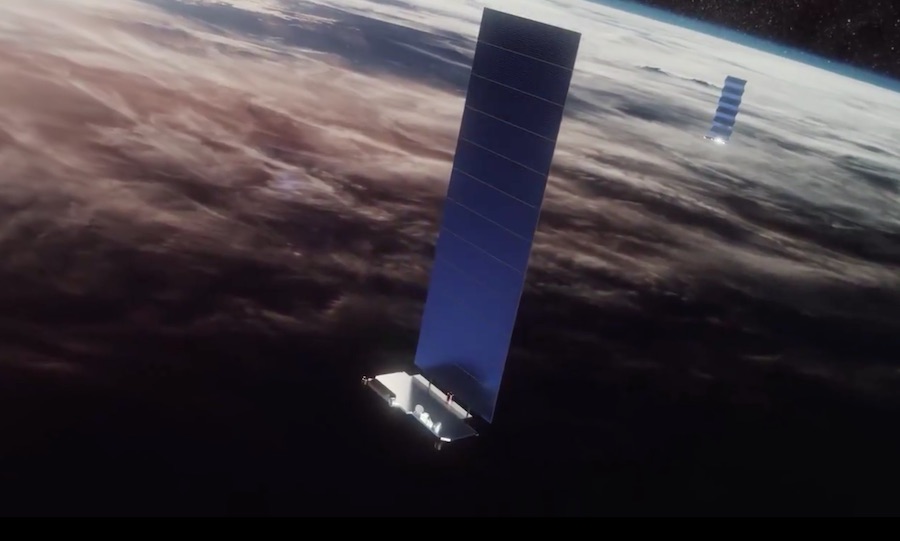

The 53 Starlink spacecraft launched on Friday’s mission will unfurl solar arrays and run through automated activation steps, then use krypton-fueled ion engines to maneuver into their operational orbit.

The Falcon 9’s guidance computer aimed to deploy the satellites in an elliptical orbit between 144 and 209 miles in altitude, at an orbital inclination of 53.2 degrees to the equator. The satellites will use onboard propulsion to do the rest of the work to reach a circular orbit 335 miles (540 kilometers) above Earth.

The launch Friday was the first to place Starlink satellites into a lower-altitude elliptical transfer orbit since February, when aerodynamic drag produced by a solar storm caused nearly 40 Starlink satellites to re-enter the atmosphere shortly after launch. Since then, all of SpaceX’s Starlink launches have included two burns by the upper stage engine to climb to a higher orbit closer to the Starlink operational altitude for spacecraft deployment.

Barry Goldstein, a SpaceX engineer, said last month in a presentation to the Federation of Astronomical Societies that the Starlink team made changes to guidance, navigation, and control algorithms to handle higher aerodynamic drag, allowing SpaceX to move the Starlink injection altitude lower again.

SpaceX is also working with NOAA and NASA to better estimate atmospheric density by providing the government agencies with drag measurements from Starlink satellites, Goldstein said.

“We have a lot of sensors in space, so we’re working with NOAA to potentially provide our atmospheric drag acceleration estimates in order to de-bias some of the modeling that they do for atmospheric drag,” Goldstein said.

Once at their operational altitude, the Starlink satellites will fly in one of five orbital “shells” used in SpaceX’s global internet network. After reaching their operational orbit, the satellites will enter commercial service and begin beaming broadband signals to consumers, who can purchase Starlink service and connect to the network with a SpaceX-supplied ground terminal.

With the 53 satellites launched Friday, SpaceX has sent 2,706 Starlink spacecraft into orbit since 2018, including prototypes and test units no longer in service. Data collected by Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist and expert observer of spaceflight activity, indicates SpaceX currently has more than 2,400 Starlink satellites in orbit, as of Friday.

SpaceX is in the middle of deploying an initial fleet of around 4,400 Starlink satellites to provide continuous low-latency broadband service around the world, and has announced plans to operate as many as 42,000 satellites.

Other companies are also in the market to provide broadband service from satellite fleets in low Earth orbit. OneWeb has launched 428 satellites of its planned constellation of 648 spacecraft, and Amazon is developing the Kuiper constellation, which could number 3,200 satellites.

Other satellite operators are in the earlier stages of developing large constellations, including Chinese companies.

Scientists are concerned the growing number of satellites orbiting close to Earth will interfere with astronomical observations.

SpaceX’s first batch of 60 Starlink satellites were brighter than expected, reflecting sunlight down to Earth’s surface after dusk and before dawn, shining bright enough to be easily seen with the naked eye. The company responded to astronomers’ concerns by adding darker coatings and a sunshade to Starlink satellites, making them less reflective of sunlight.

The changes dimmed the Starlink satellites to about magnitude 6.5, approaching the magnitude 7 threshold, the limit where a human with good vision and a dark sky might be able to spot the spacecraft as they fly overhead, according to Pat Seitzer, an astronomer and orbital debris expert at the University of Michigan.

“I think we were all very, very pleased with the progress that SpaceX had made there,” Seitzer said.

The 7th magnitude threshold set by astronomers would also allow streaks made by Starlink satellites to be removed from the most sensitive ground-based telescopes, such as the Vera Rubin Observatory. The observatory under construction in Chile will capture deep, wide-field images of the entire southern sky, allowing astronomers to learn more about dark energy and dark matter, and detect potentially hazardous asteroids with orbits near Earth, among other objectives.

But SpaceX has removed the sunshade visors from a new generation of Starlink satellites that began launching last year. The visors would have blocked laser inter-satellite links on the new satellites, a new capability SpaceX introduced to allow the Starlink nodes to pass data to one another without relaying signals to a ground antenna.

“The most recent observations suggest that the new generation of Starlinks that have the visors removed … they’re about a half a magnitude brighter,” Seitzer said. “The new satellites are about a factor of two-and-a-half fainter than the original ones, so they’re coming in at about 6th magnitude.

“Things are going in the wrong direction,” Seitzer said. “We’ll have to see what magic SpaceX can perform in terms of the surfaces that they use, the orientation that they fly in. They made a commitment to the astronomical community to try to reach that 7th magnitude goal.”

SpaceX has adjusted the pointing angles of the Starlink satellites to minimize reflectivity, and is continuing to work on other mitigations to darken the satellites, Goldstein said last month.

Goldstein said SpaceX is transitioning to the use of “specular material” on the Earth-facing deck of the Starlink satellites to reflect light away from the ground, instead of mounting the sunshade visors on each spacecraft. The company is investing “quite significantly” in dielectric mirrors to make reflected sunlight less diffuse.

SpaceX is also working on developing dark paint that is qualified for the harsh environment of space and is committed to publishing regularly-updated orbit data so astronomers will know where the Starlink satellites are located in the sky.