The two Nordic states have long maintained military neutrality, but that changed in February 2022 when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine – the biggest war on the European continent since World War Two.

Why join now?

Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion shattered a long-standing sense of stability in northern Europe, leaving Sweden and Finland feeling vulnerable.

Finnish ex-Prime Minister Alexander Stubb said joining the alliance was a “done deal” for his country as soon as Russian troops invaded Ukraine last year.

For many Finns, the war brought a haunting sense of familiarity.

It was in late 1939 that the Soviets invaded Finland. For more than three months the Finnish army put up fierce resistance, despite being heavily outnumbered. Finland held out until March 1940 but lost its eastern province of Karelia to Russia.

They avoided occupation but ended up losing 10% of their territory.

Watching the war in Ukraine unfold was like reliving this history, said Iro Sarkka, a political scientist at the University of Helsinki. Finns were looking at their 1,340km (830 miles) border with Russia, she said, and thinking: “Could this happen to us?”

Sweden has also felt endangered in recent years.

Sweden’s military weakness came into full view in 2013 when Russian bomber planes were able to simulate an attack on Stockholm and Sweden needed Nato help to ward them off.

In 2014, Swedes were transfixed by reports that a Russian submarine was lurking in the shallow waters of the Stockholm archipelago.

In 2018, every household received army pamphlets titled “if crisis or war comes” – the first time they were sent out since 1991.

How big are their military forces?

For a population of only 5.5 million, Finland’s conscript military is highly trained and potentially large. It trains at least 21,000 conscripts every year and has a reserve force of 900,000, so its wartime strength is estimated at 280,000.

Sweden’s military capacity is far smaller at 57,000. But it brought back conscription at the start of 2018, after suspending it in 2010, and the current number of up to 6,000 conscripts will rise to 8,000 in 2025.

From the 1990s Sweden cut back the size of its military and changed its priorities from territorial defence to peacekeeping missions around the world. But that went into reverse with Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 and its increasing threat in the Baltic region.

What will change?

In some ways, not much. Sweden and Finland became official partners of NATO in 1994 and have since become major contributors to the alliance. They have taken part in several Nato missions since the end of the Cold War.

The two countries will for the first time have security guarantees from nuclear states under Nato’s Article 5, which views an attack on one member state as an attack on all.

Historian Henrik Meinander said Finns were mentally prepared for membership, following a succession of small steps towards Nato since the fall of the Soviet Union.

In 1992, Helsinki bought 64 US combat planes. Three years later, it joined the European Union, alongside Sweden, and every Finnish government since then has reviewed the so-called Nato option.

Finland has already reached Nato’s agreed defense spending target of 2% of GDP, and Sweden has drawn up plans to do so by 2026.

Sweden may have been neutral during the Cold War but at the time it kept a force of at least 15,000 soldiers on the Baltic island of Gotland and has recently rebuilt its presence there. It hopes to build up its full-time military as well as its conscript force in the coming years.

What are the risks?

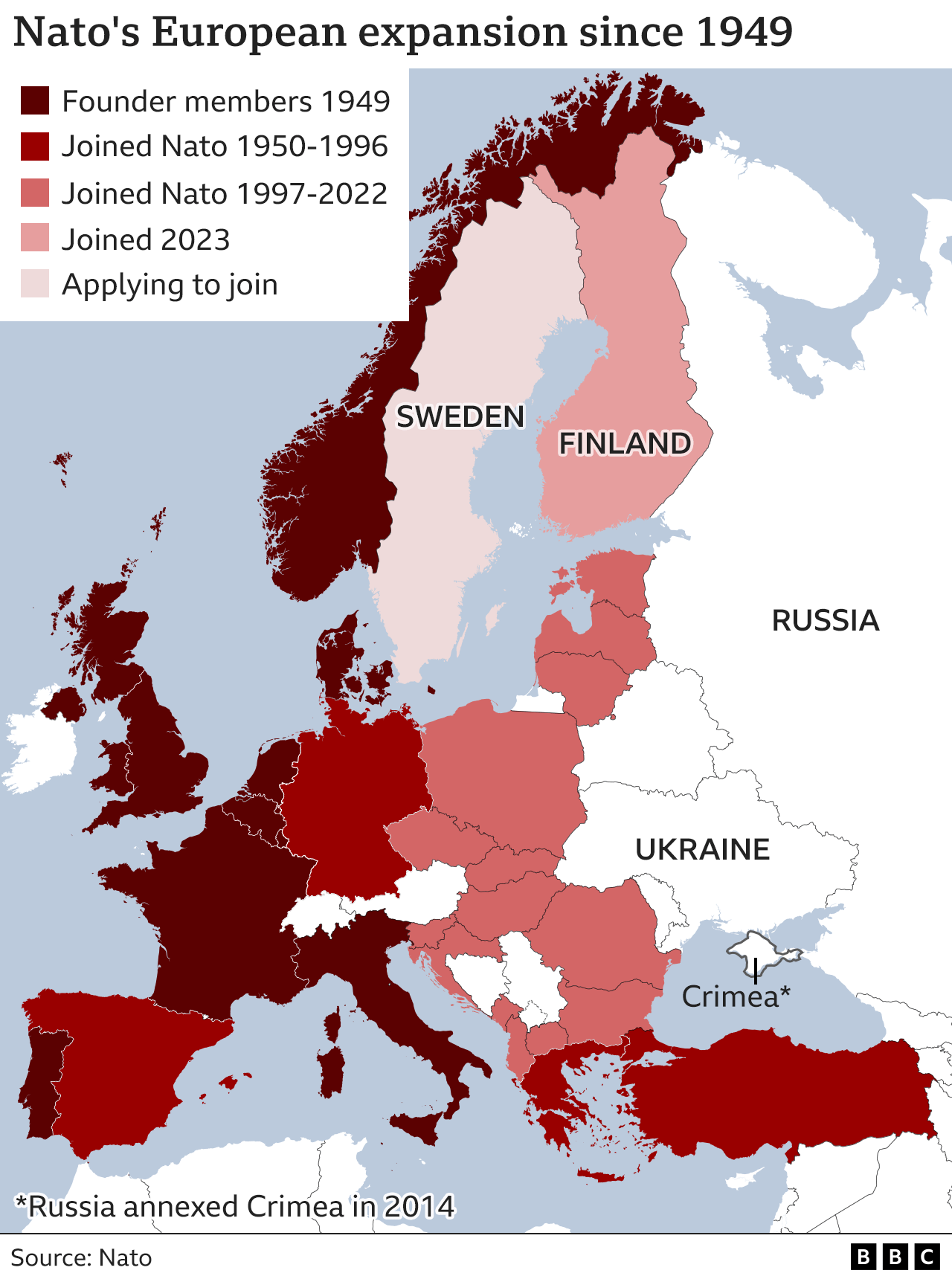

Russian President Vladimir Putin believes Nato expansion is a direct threat to his country’s security – and claimed it was the reason he launched the 2022 war in Ukraine. But his invasion had the opposite effect by only serving to extend Nato’s reach.

Finland’s accession was a particular setback, further extending NATO’s influence over the Baltic Sea. And it brought a warning from the Kremlin of unspecified “military-technical” measures in retaliation.

Russia’s foreign ministry said both Sweden and Finland had been warned of the consequences if they did choose to join.

Now that Sweden has been given the green light by Turkey to become a member, the Kremlin has said it will respond with the same kind of measures it proposed for Finland.

What those measures would be is still vague. Russia says it has moved tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus, and they could reach Finland and Sweden.

But former Finnish PM Alexander Stubb has warned that Russian cyber attacks, disinformation campaigns and occasional airspace violations are more likely.

Will Nato make Sweden and Finland safer?

Under Article Five, Finland has – and Sweden will – soon have the commitment of the entire alliance to come to their aid if they come under attack. Their membership also makes defending the Nordic and Baltic regions far more comprehensive.

But there is a significant minority, at least in Sweden, who believe membership will have an adverse effect.

Deborah Solomon, from the Swedish Peace and Arbitration Society, argued that NATO’s nuclear deterrence increased tensions and risked an arms race with Russia. This complicated peace efforts, she said, and made Sweden a less safe place.

Another fear is that in joining the alliance, Sweden would lose its leading role in global nuclear disarmament efforts. Many of Sweden’s Nato-sceptics look back to the period between the 1960s and ’80s, when Sweden used its neutrality to position itself as an international mediator.

Joining NATO would be abandoning that dream, Ms Solomon said.

Finland’s neutrality was very different. It came about as a condition of peace imposed by the Soviet Union in a 1948 “friendship agreement”. It was seen as a pragmatic way of surviving and maintaining the country’s independence.

If Sweden’s neutrality was a matter of identity and ideology, in Finland it was a question of existence, said Henrik Meinander. Part of the reason Sweden could even afford to have a debate about Nato membership was that it used Finland and the Baltics as a “buffer zone”, he said.

Finland abandoned its neutrality after the Soviet Union collapsed. It looked to the West and sought to free itself from the Soviet sphere of influence.

Why Turkey resisted Sweden and Finland

Turkey, and to a lesser extent Hungary, initially resisted both applications.

Ankara accused the Nordic nations of supporting what it called terrorist organizations, including the Kurdish militant PKK and the Gulen movement, which Turkey blames for an attempted coup in 2016.

Kurds make up 15-20% of Turkey’s population, and have been persecuted by Turkish authorities for generations.

But it was Sweden that triggered most hostility as Kurds have mobilised successfully in politics there over the decades.

President Erdogan asked how “how a country with terrorists on the streets… can contribute to Nato”.

His main demand was to end political, financial and “arms support” to militants.

Sweden updated its terror laws in June 2023 to outlaw taking part in an extremist group in a way that supported it – and weeks later a Kurdish man was jailed for attempting to finance terrorism.

But there was some suggestion, denied by Turkey, that its main reason for resisting Sweden’s bid was that Ankara was waiting for the US to provide F-16 fighter jets.

Source: bbc.com