By Phillip Meilinger

Prior to 1939, Airmen dreamed the airplane could eliminate the horrors of war. Instead of impaling a generation of young men on barbed wire in Flanders, airpower would humanize war, making it less likely to occur in the first place, and when it did, ensuring it would be over quickly. It was a false hope, in the end. The hecatomb of World War I was not avoided; the trenches were merely moved to 20,000 feet.

The history of the Army Air Forces (AAF) in World War II has been the subject of continuous review over the past seven decades, and has enjoyed a popular revival in 2024 with the airing of “Masters of the Air,” a dramatic miniseries based on the book of the same title. The similarities to the international stressors that led to World War II and those of today have also given rise to increased interest in the period.

Following World War I, the U.S. retreated into an isolationist shell: America sought a return to normalcy, imposing hard times on the armed forces even before the Great Depression. The Army suffered budget cuts through the 1920s and ’30s, and its nascent Air Service (renamed the Air Corps after 1926) suffered worse. Between the wars, the air branch received, on average, less than 12 percent of the Army’s budget, and as late as 1939 only one Airman had reached general officer rank on the permanent list. These slights so infuriated Col. Billy Mitchell that his ensuing outspoken condemnations of his superiors led to his court-martial. The air arm was severely deficient in combat aircraft, especially bombers, so that when war broke out in Europe in September 1939, the Air Corps possessed fewer than 30 B-17s. Mobilization was rapid; some 21,000 aircraft were purchased over the next two years, yet only 373—just 1.8 percent—were heavy bombers. For the interwar years, Maurer Maurer’s Aviation in the U.S. Army, 1919-1939 (Office of Air Force History, 1987) and DeWitt S. Copp’s A Few Great Captains (Doubleday, 1980) tell the story. For procurement details see I.B. Holley, Buying Aircraft: Materiel Procurement for the Army Air Forces (GPO, 1964), and Jeffrey S. Underwood, The Wings of Democracy: The Influence of Air Power on the Roosevelt Administration, 1933-1941 (Texas A&M University Press, 1991).

To redress deficiencies in the air arm, Billy Mitchell founded the Air Corps Tactical School (ACTS) at Maxwell Field, Ala.

Just about anyone who would be anyone in the air arm during World War II attended ACTS earlier in their careers; many taught there, including Hoyt Vandenberg, George Kenney, Muir “Santy” Fairchild, Pat Partridge, Larry Kuter (all of whom later became four-stars). Lieutenants and captains in their teaching days, they imbibed the heady ideas of their intellectual mentor, Billy Mitchell, and devised the theory of precision strategic bombing as a means to defeat an enemy’s industrial capacity to win, to destroy its vital centers, rather than fight bloody land battles that consumed a country’s youth by the millions. They would fly over these deadlocked armies and quickly achieve decisive results.

In the European theater, this meant an invasion of Axis-held North Africa in November 1942. Airpower would be crucial to any such amphibious landing, but there were precious few airplanes and crews to spare. The 8th Air Force, which was building in England to bomb targets in Germany, was denuded to supply the new 12th Air Force that would support Operation Torch in North Africa. The code name for the 12th, appropriately and cynically, was “Junior.” Maj. Gen. Ira Eaker, commander of the 8th, protested this diversion of his resources, but was overruled.

From there, the Allies moved across the Mediterranean to attack Sicily, a prelude to invading Italy proper. Italy was seen by some as a minor theater—the real enemy was Germany, which was most easily confronted in France. But the Allies were not yet ready for a French invasion and Italy was believed so weak that a determined shove could knock it out of the war. Indeed, after the bombing of Rome’s rail yards in July 1943, Benito Mussolini, prime minister of Italy, was overthrown, prompting Germany to flood troops into Italy and take over. In the southern part of the peninsula, a new air force, the 15th, stood up to fly ground support and bomb Germany. For the story, see Robert S. Ehlers Jr., The Mediterranean Air War: Airpower and Allied Victory in World War II (University Press of Kansas, 2015), DeWitt S. Copp, Forged in Fire (Doubleday, 1982), and Christopher M. Rein, The North African Campaign: U.S. Army Air Forces from El Alamein to Salerno (University Press of Kansas, 2012).

The heavy bombers of the 8th AF based in England were mostly B-17s. Because fighters of that era could not match bombers’ range, the bombers had to go it alone much of the time, flying in large formations of hundreds of bombers—each aircraft armed with 10 machine guns to combat enemy fighters. Antiaircraft artillery threw up flak that proved the bombers’ most dangerous threat, causing over 70 percent of bomber crew casualties, but was immune to the bombers’ defenses. For this story, see Edward B. Westermann, Flak: German Anti-Aircraft Defenses, 1914-1945 (University Press of Kansas, 2001).

A unique aspect of air warfare made coping even harder. Combat was episodic—crews experienced enemy fire for three or four hours, then returned home to repeat the ordeal a few days later. Bad weather could stretch down time to a week or more.

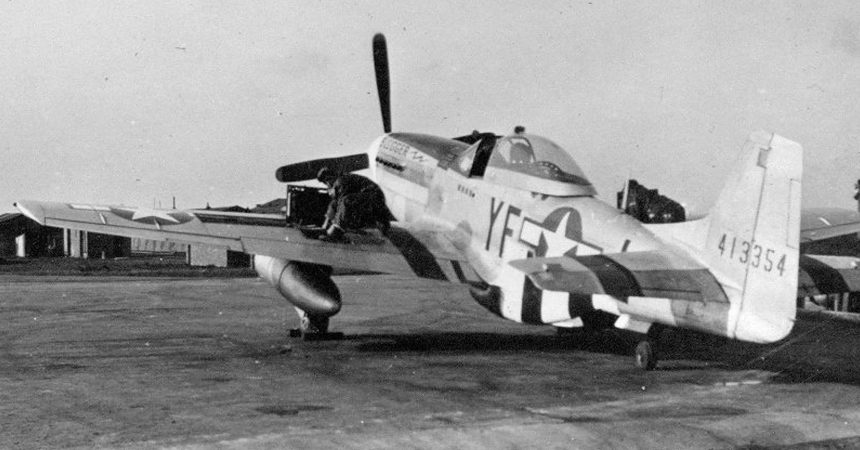

Fighter pilots always get the glamour, a fact established in the Great War and solidified in the Second. Aces—those with five aerial victories—became public heroes—in all countries. In Britain they were known as “The Few,” and in Germany they received special decorations, the highest being the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds. American aces were no less heralded. Although the top two U.S. aces flew in the Pacific, the European theater had its share of legends: Francis “Gabby” Gabreski, Robert Johnson, George Preddy, Hubert “Hub” Zemke, and Don Gentile among others.

But protecting bombers implied a passive, defensive mission that would rob them of the initiative. Fighter instructors at ACTS, notably Claire Chennault and Hoyt Vandenberg, rejected the notion of escort. That was a mistake.

Bombers suffered horrendous losses in late 1943, demanding creative solutions. The answer proved surprisingly simple: Fighter planes were fitted with external fuel tanks under their wings. When the tanks ran dry, they were jettisoned—and the planes flew on with their full complement of internal fuel. Without tanks the P-47 could fly out 230 miles; with tanks range increased to 475 miles. When the P-51 Mustangs added drop tanks, range grew even more, from 475 to 850 miles. By the end of the war the Mustangs could fly all the way to Vienna—farther than B-17s!

When Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle took over the 8th AF in early 1944, a sign at fighter headquarters read: “Your duty is to protect the bombers.” He replaced it with another: “The first duty of Eighth Air Force fighters is to destroy German fighters.” This semantic change made it the fighter pilots’ mission to aggressively seek out and destroy the enemy air force wherever and whenever they found it.

Approximately 33,000 American Airmen were captured by Germany and Italy during the war, and these prisoners of war (POWs) were sent to camps called Stalag Lufts. The most famous of these, Stalag Luft III, held over 10,000 Allied air officers.

The Luftwaffe, which ran the camps for Allied Airmen, was less rigid than its ground counterparts. But when 80 men escaped in March 1944 from Stalag Luft III in the “Great Escape” of legend, only three of the men made it to Britain. Of the 77 remaining, all were recaptured and 50 were summarily executed by the Gestapo, the worst such atrocity of the war for Allied Airmen in Europe.

Strategic bombing was a form of economic warfare, so it was necessary that air planners understand how the enemy economy functioned—and how to break it. Bombers could hit just about anything, but targeting was key.

In one study, post-strike photographs revealed that bombing accuracy was enhanced if an entire group dropped when its leader did, rather than if each bombardier chose his own drop point. Another problem involved the relative danger of enemy interceptors versus flak. The worst situation existed for stragglers: When a bomber fell out of formation, typically due to flak damage, enemy fighters quickly pounced. Adding armor to the engines reduced the problem stragglers.

In the planning for the Normandy invasion in early 1944, American analysts argued that oil should become the top priority target. If the oil refineries and hydrogenation plants were knocked out, the enemy war machine would halt. RAF planners saw the German rail network as the primary focus. Troops, supplies, equipment and raw materials all moved primarily by train. If the rail lines were cut and trains stopped, especially in France, it would be difficult for the Germans to resupply the coast.

There is a bit more to the story. In January 1945 the German rail system, which had been employing its own teletype network for transmitting status reports, began using the top-secret Enigma machine because its teletype system and landlines had been knocked out by bombing. Allied intelligence had ignored rail messages, believing them of little importance, but when it began using Enigma—not by design but necessity—analysts started paying attention. Enigma revealed the crucial role played by coal in the German economy, powering 90 percent of industrial production. More to the point, coal was moved largely by train. Since the rail plan had been in effect, coal shipments had slowed, causing a serious decline in German production. The implication was clear. To deliver a death blow to German industry and military capability, one had to stop the flow of coal, and that meant stopping the trains.

The United States spent $183 billion on armaments during World War II, and the AAF share was $45 billion (24.6 percent). With that money it bought 230,175 aircraft, of which 34,625 were heavy bombers (15 percent). These bombers cost $9.2 billion—20.4 percent of AAF expenditures and 5 percent of the U.S. total. Whether the taxpayer got his money’s worth has been debated for decades, but the arguments shed more heat than light. There was, however, a massive effort conducted at the end of the war to answer the question of strategic airpower’s effectiveness: the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS). Its findings are difficult to dispute because of the massive amounts of facts and details that were uncovered and recorded.

Franklin D’Olier, president of Prudential Insurance, led the project, which eventually included 1,600 officer, enlisted, and civilian personnel, all led by civilians. Most of these were picked for their specific expertise: a Standard Oil executive for the oil division, the director of U.S. Civil Aeronautics for the aircraft division, etc. The survey’s military advisers included Gens. Omar Bradley and Lucius Clay and Adms. Richard Byrd and Robert Ghormley.

USSBS presented scores of charts, graphs, and tables illustrating the impact of bombing. At its peak, the Allied air campaign employed 1.34 million personnel and over 27,000 aircraft. Bombers flew 1.44 million sorties and dropped 2.7 million tons of bombs—54.2 percent by the AAF and the remainder by the RAF. The bombing campaign was costly—nearly 160,000 Airmen were lost by the British and the Americans combined. Significantly, 85 percent of all bombs dropped by the AAF on Germany fell after D-Day. In truth, the Combined Bomber Offensive did not really begin until the summer of 1944—the third year of war for the Americans and fifth for the British.

Bombing attacks on the German transportation system were critical: 40 percent of all rail traffic was coal—21,400 train carloads per day at the beginning of 1944, but by the end of the year that number had fallen to 9,000 cars daily. Rail traffic in general had nosedived 50 percent by mid-1944. Steel production suffered an 80 percent drop in three months.

The survey argued that air superiority was essential to the bombing campaign’s success. This air dominance was not achieved until early 1944 (the “Big Week” air campaign mentioned earlier), allowing the bombing campaign to achieve its dramatic results. Indeed, it is important to remember that the invasion of France was pushed back from 1942 to 1943 and finally occurred in June 1944—a major reason for this delay was that air superiority over the beachhead was deemed essential for success.

USSBS is a subject overlooked by most historians. A total of 215 reports were written for Europe, but only the overall summary report has been published by Air University Press and been readily available to interested observers. David MacIsaac, Strategic Bombing in World War Two: The Story of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Garland Publishing, 1976), wrote an excellent account of the survey apparatus itself. Garland then published seven volumes containing 31 of the most important reports, including summaries of the major targeting divisions: oil, aircraft, munitions, morale, etc. These are an invaluable source—if you can find them. For a comparison, see the bombing report done by the RAF, Sebastian Cox, ed., The Strategic Air War Against Germany, 1939-1945 (Frank Cass, 1998).

The subjects of legality and morality often arise when discussing the bombing campaign. The two are separate, but related. Legally, the issue is surprisingly simple: There was no law specifically addressing bombing going into World War II. As a result, air commanders adapted existing laws dealing with war on land and sea.

The law also permitted navies to shell undefended fortresses and cities to destroy their military stores and facilities—even if this meant the death of civilians inside (Cherbourg). Because navies could not occupy a port as could an army, Sailors were given wider latitude in shelling civilians. Aircraft, like ships, could not occupy a city, so the permissive rules of sea warfare seemed more applicable to air war.

Was that targeting strategy justified? Philosopher Michael Walzer examined the issue and decided it was—at least initially. British leaders argued that a combination of reprisal and military necessity made city bombing acceptable. Walzer considered the military necessity rationale. A Nazi triumph was too awful to contemplate, and he conceded that in the dark days of 1941, before Russia and America entered the war, the future looked bleak for Britain. Its army had been thrown off the continent at Dunkirk, and the Royal Navy was fighting for its life against Nazi submarines in the Battle of the Atlantic. Britain’s only hope of hurting Germany and achieving victory was through strategic bombing. Given the inaccuracy of Bomber Command’s night strikes, it was obvious thousands of civilians would die if such a strategy was employed. Viewing this as an instance of “supreme emergency,” Walzer concluded that such a strategy was morally acceptable. However, this justification declined as the war progressed and it was clear the Allies would eventually win.

How many noncombatants died? One expert states that of the 60 million people who died during the war, two-thirds were civilians. But statistics gathered by experts show that fewer than 2 million civilians died as a result of bombing—worldwide. If correct, that means 95 percent of all the noncombatants killed during the war were the result of land and sea operations, not air warfare. There is a rich literature on the subject, especially M.W. Royse’s Aerial Bombardment and the International Regulation of Warfare (Harold Vinal, 1928), Michael Howard’s Restraints on War: Studies in the Limitation of Armed Conflict (Oxford University Press, 1979), and Micheal Clodfelter, Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualties and Other Figures, 1618-1991 (McFarland & Co., 1992).