WASHINGTON: Nearly every time a flag officer or senior civilian in the US Navy has been called to testify before lawmakers about the Constellation-class (FFG-62) frigate recently, there is one talking point that always comes up.

The use of a “parent design” — modeling the new ship’s hull form off a pre-existing, already proven vessel — will reduce the risk the Navy assumes when it begins construction, they say.

That idea has been at the core of the service’s response to lawmakers who raise concerns about the new vessel repeating the trials and tribulations of the Littoral Combat Ship, a program beaten to a pulp by Congress and analysts alike for the delays and cost overruns it suffered.

But the service’s reliance on this talking point elides a reality of every shipbuilding program: No matter how good a parent design may be, changes are always necessary to build the ship the service wants. That fact raises questions about how much the Navy, or a private shipbuilder, can tweak and tinker with a new vessel before the benefits of modeling off a proven warship begin to erode.

Experts told Breaking Defense that not all changes are as inherently risky as they might seem, and the Navy appears to have heeded lessons from previous controversies.

But for the new frigate, they said the Navy must balance the changes it needs to build a capable warship with ones that could imperil the production schedule — and untold taxpayer dollars — if problems arise.

“In terms of changes from a parent design… as you start to drive further away from a parent design, there is the risk of cost increase, especially if you have immature equipment that requires testing or fails testing,” said Steven Wills, a Navy strategy and policy expert at CNA, a federally funded research and development center that provides advice to the Pentagon.

The Constellation-class frigate will be built by Wisc.-based shipbuilder Fincantieri Marinette Marine. That firm used the FREMM, a class of multi-purpose European frigates designed and built by FMM’s Italian parent company, as the parent design in its April 2020 proposal to the Navy. To date, the shipbuilder has been selected to build the first 10 vessels in the class, a deal worth roughly $5.5 billion.

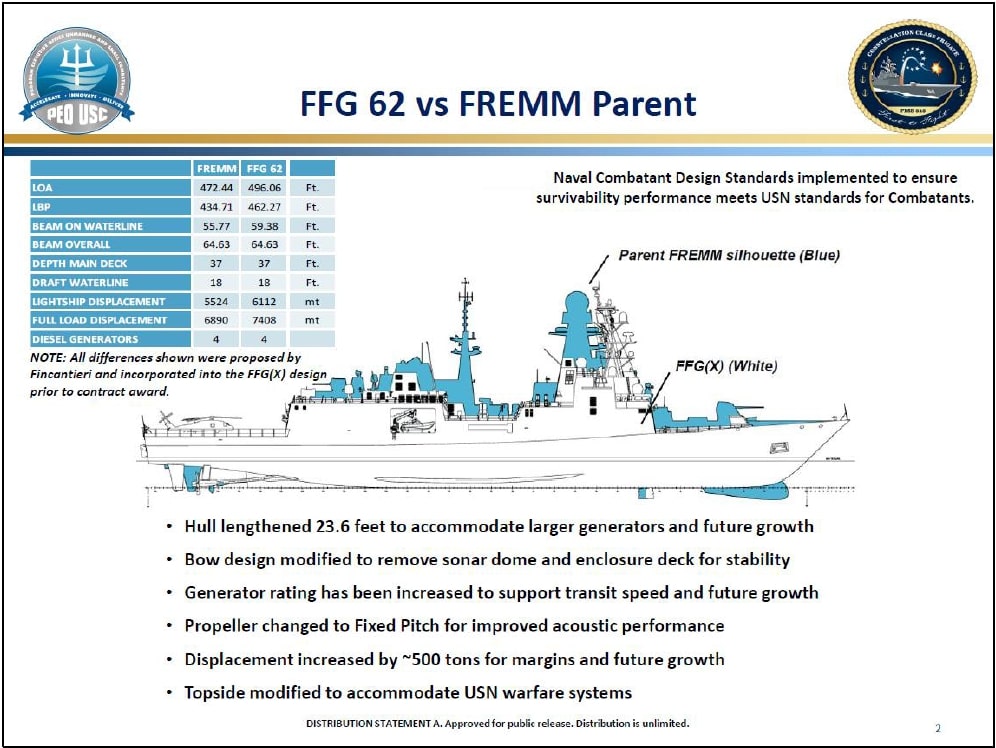

Some of the changes FMM made between the FREMM and its version of the Constellation are highlighted in a September 2021 report by the Congressional Research Service. They include lengthening the hull by 23.6 feet, increasing the ship’s displacement by 500 tons and various topside modification for weapon systems, among other things.

A US Navy slide outlining differences between the Constellation-class frigate and the Italian FREMM. (Source: Congressional Research Service)

When asked this month at the Surface Navy Association’s annual symposium about how those changes could impact the program’s risk calculus, Capt. Kevin Smith, the Constellation-class program manager, said the parent design is a starting point, but nothing more.

“I think it was clear to everyone in Navy leadership as well as congressional leadership that the parent is there as just that… think of it as a DNA,” he said. “But you do have to take US Navy standards and apply those, and also the requirements.”

In other words, if the Navy wanted to buy a FREMM, it could have, but that’s not the objective. Currently the Constellation class is in its detailed design phase, in which the Navy and Fincantieri are working to finalize enough of the ship’s layout before starting construction.

This part of the program’s life is important because the Navy never waits until a ship’s design is complete to begin building — a potentially time-saving strategy, but one with real consequences to the program’s schedule if the trigger is pulled too early.

“The only thing that we’ve [the Navy] done actually — it’s a change to the requirements — is buy American, because that was a statute from Congress,” Smith said, referring to legislation mandating certain parts and percentages of US warships be manufactured domestically.

Through a spokesman, Fincantieri Marinette Marine leadership declined to be interviewed for this article.

Changes Are Good… If You Choose Wisely

Where does that leave the Navy? The service must decide what changes make sense to accommodate its needs and what may be a step too far, experts told Breaking Defense.

The Gerald Ford-class aircraft carrier is one example of the danger. Lawmakers in recent years have hammered the Navy over setbacks on a variety of new technologies being brought onboard that vessel, such as the Advanced Weapons Elevators.

But CNA’s Wills said one major difference between the FREMM and the Constellation, the elongated hull form, is not surprising because of differences in how Europeans and the United States go about building warships.

The Navy chose a version of the Italian Bergamini-class ship for the parent design of its new frigate. (file)

“You don’t incur a lot of costs in making the ship bigger. That shouldn’t slow you down. That shouldn’t cause testing to fail,” he said. “You’re going to have to buy more steel and there will be some changes. The benefit that they seem to be going for… is they’re looking for some additional margins throughout the life of the ship.”

Matthew Collette, who teaches naval architecture and marine engineering at the University of Michigan, said fully adopting a parent design without modification is “exceptionally rare” especially for the US Navy, which has developed standards for internal layouts and adheres to congressional policy dictating supply chain options.

“Changing the overall dimensions of the ship is probably lowering the overall risk to the program, not raising it,” Collette told Breaking Defense. “Given that we are changing the internals of the design, adhering strictly to the old hull form would actually increase the overall risk to the program, as you end up adding complexity by trying to shoehorn in components in a less-than-ideal layout.”

He cited the Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Whidbey Island-class dock landing ships as examples where Navy programs have historically suffered because the service attempted to maintain the ships’ external design while altering its internal layout.

Collette said there are three principles a shipbuilding program should follow to reduce the risk of modifying a parent design. The first is choosing proven systems when swapping out components. In the Constellation’s case, the Navy has done just that by choosing systems such as Aegis, the Mk 41 Vertical Launching System and the SLQ-32 from the Surface Electronic Warfare Improvement Program.

The second principle is to thoroughly test new components ashore, a requirement Congress codified in law after finding out the Navy failed to do this on other systems that proved troublesome for the Ford.

The last principle is having a completed definition of the parent design, such as a 3D model, a parameter for which Collette and other analysts have no way of assessing from outside the Navy’s program office.

“Even with some changes, the program is still benefiting from access to the original design models, and the knowledge gained in building and operating vessels that are highly similar, but no longer exactly the same, to the US Navy variant,” Collette said.

Constellation (FFG-62) is scheduled for delivery to the Navy in 2026. With its arrival the US Navy will mark an official comeback for the frigate to its surface force, a type of warship the Pentagon has not commissioned since before the turn of the millennia — assuming, of course, it can be delivered on time, something that may well be determined by how the Navy pulls off its hull changes.